In You, I Make My Home

- Nasreen Khan

- Sep 18, 2018

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 24, 2020

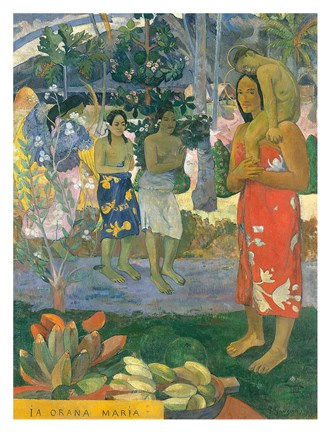

Some thoughts on colonialism, clasism, colorism and finally coming home. What does home mean in times of political instability, racism, and inequality?

The hygge movement here in the US was gaining momentum around the time that I was home with my newborn son, scared that I would not create the home he needed. Hygge was the briefly trendy Danish concept of warmth and coziness as lifestyle. Parenting blogs and women’s groups seemed to constantly be presenting the idea of an ideal home as a cozy oasis in an oatmeal and gray palette, tinged with heteronormativity and affluence. As a new parent, still in graduate school, that idea was terrifying.

Growing up, home was a complicated concept that was entwined with colonialism, colorism and classism simultaneously. I come from a line of nomads. My father converted to Christianity as a teen and was ostracized by his Muslim family so he left Afghanistan at 16, walked across the Khyber Pass into Pakistan on foot and never returned. My parents are both bi-cultural. My father is Afghan-Russian and my mother is Chinese-Filipino. They traveled as teachers in international schools so the early part of my childhood was spent in Senegal, West Africa. There I was closest to my Senegalese nanny, and did not have a close relationship with my parents. Until I was 18 I had 3 passports, and my parents always kept a go bag by the door with cash of various currencies and vital documentation, in case a political uprising should send us fleeing into the night.

I spent ages 9-16 in boarding school in Indonesia about an hour’s flight away from my parents. The boarding school was wonderful, with green grounds to roam freely, loving staff, and a rigorous educational standard…but it was mostly American and Korean missionary kids—which is to say that there were very few students that were brown like me. Even though most of the country looked like me there were a few barriers—namely, nationality and privilege. My parents were well-off foreigners who earned far more than the average Indonesian national, and colonial hierarchies were accepted as the norm. For example, my parents (both graduate degree holders with decades of teaching experience) both always earned less than new teachers with no experience who were from the USA or other western nations. Whiteness was the penultimate passport to privilege.

This concept was reinforced over and over again as I saw Australia dump its trash barges in Indonesian waters, and Western tourists were openly exploitative without repercussion. My earliest memory is screaming in a Senegalese prison as my father was locked in a deportation cell (he was let out the next morning when his [White] employer intervened). I remember a church service where the matter of whether to allow Africans to count the offering, in fear of theft, was discussed openly and without shame. All of this is to say that as a biracial brown girl, surrounded by White peers of the same economic level, and national staff who were separated from me by class and wealth, and a domestic life that had little cultural unity I didn’t quite know how to define myself, because there was no one group that I could claim (or who was willing to claim me).

As an adult, that lingering sense of otherness persisted. I became fascinated with the margins. I sought out work and people that felt comfortable in liminal space. My graduate writing examined post-colonial theory as applied to trans-gendered sex workers in Asian and African diasporic literature. Delving into the transience and instability of the characters felt like picking up the stole of childhood. But I still desperately wanted to figure out who my people were. What cultural group was mine? What traditions and histories could I claim?

After years of wrestling, I came across a line of poetry that read “home is in my morning cup of coffee”, and it felt somehow clear to me that like many other seemingly complex things, this too was a choice. Biracial, bi-cultural, bisexual—these are all identity labels that perch me on a margin that I do not choose; however, labels like—non-violent, listener, gardener, justice-maker, mother, wife, steward of the Earth —are all just as applicable to me and clear choices that I have made. I no longer feel like there is a set template I need to align with in order to be at home. I can choose spiritual inspiration from many sources. I can serve garlic shrimp, collard greens, and curried lentils for Christmas dinner, and choose to live on Indianpolis’ Westside—worlds away from the continents I grew up in, and be at home.

Here we are in Pandemic time, and those old thoughts of home are more at the forefront of my mind than ever. Spending so much time in my physical home gets me thinking about my cultural, spiritual, and ethnic homes. I am once again beginning the practice of telling myself that home is chosen; that my credo of faith is what I build it; and that my community is created from those I choose to love. In all of you, I find my home as well.

I would love to hear your thoughts on how you choose your homes.

Comments